ALLAN RAY

God Speaks Through Multiple Channels

Many are turned away by the idea of an emotional dictator who lives in the sky, but what if we could explain things differently?

ALLAN RAY

Many are turned away by the idea of an emotional dictator who lives in the sky, but what if we could explain things differently?

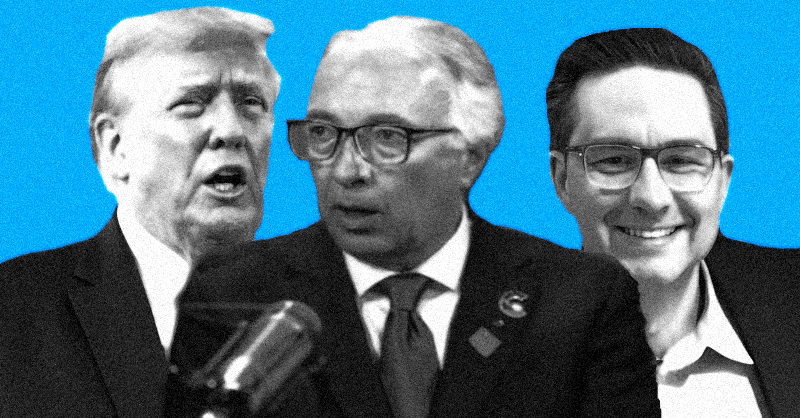

NICK EDWARD

Trump played the media and his targets like fools, knowing they would build a mountain out of his mole hill.

These glaring problems suggest something different.

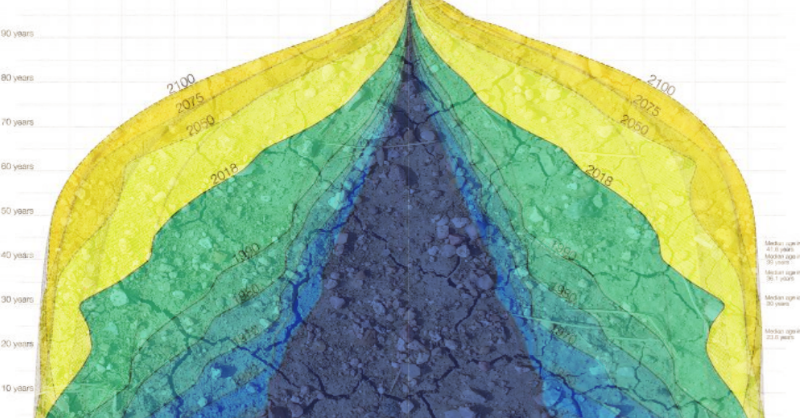

ALLAN RAY

When you see it, you should be worried about your country's future.

RYAN TYLER

But what if we applied some feminist logic to these less convenient gender gaps?

GRANT JOHNSON

Liam and Noel have said and done some controversial things, but the band is reuniting for an album and world tour.

NICK EDWARD

If the unthinkable were to become reality, much of it might go exactly how we would have expected.

RYAN TYLER

What's happening in BC offers insight into what's happening around the rest of the country.

JOHN MILLER

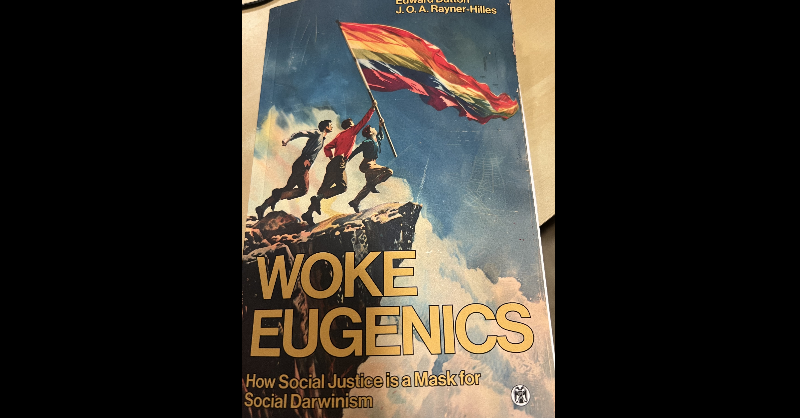

The woke will go extinct as the survivors become ultra based. Is wokeness fixing civilization?

ALLAN RAY

Russia's KGB strongman is popular and has managed to make his country a self-sustaining global force.

DEVON KASH

If you like unravelling supernatural mysteries and ingesting some traditional conservative themes, you're going to like this one.

RYAN TYLER

A second shooter on a water tower? An FBI director in the crowd? Some of these theories are off the wall.

DEVON KASH

Even Kamala Harris is rumoured to be ready to jump in bed with the crypto industry before September.

ALLAN RAY

Violence has no place in a system designed around elections, peaceful transitions of power, and bloodless coups.