ALLAN RAY

David Eby Is Sacrificing Prosperity For Ideology

He doesn't appear to oppose all pipelines and mining projects, only the ones from places with people he doesn't agree with.

ALLAN RAY

He doesn't appear to oppose all pipelines and mining projects, only the ones from places with people he doesn't agree with.

JOHN MILLER

POSTCANADIAN

Which federal party best aligns with your vision? Find out with ten simple questions.

ALLAN RAY

Can we trust childless people to lead us into a future they might not really care about?

RYAN TYLER

There was a smarter way to do it, and Danielle Smith's fatal mistake may have secured the next election for the NDP.

ALLAN RAY

It turns out, years of performative politics and reconciliation rituals have consequences.

POSTCANADIAN

Which federal party best aligns with your vision? Find out with ten simple questions.

ALLAN RAY

Liberal and NDP voters are plagued by depression and neuroticism by statistically higher margins.

THOMAS CARTER

They had one goal: to permanently silence the people who challenged their worldviews with contrary ideas.

STEVEN PARKER

From toilet paper shortages to public assassinations, few of us are the same people we were five years ago.

POSTCANADIAN

Can you handle the hypocrisy and hilarity of the woke left?

POSTCANADIAN

Which federal party best aligns with your vision? Find out with ten simple questions.

GRANT JOHNSON

Watching Canadians react to the ongoing political and economic chaos in their country is astonishing.

DEVON KASH

The old strategies have failed four times. Are Conservative voters willing to risk a fifth?

STEVEN PARKER

A BC nurse and an Ontario homeowner had to learn the hard way.

NATHAN DANIEL

Canada sits on some of the world's most powerful strategic tools, but it can't use any of them.

POSTCANADIAN

Can you handle the hypocrisy and hilarity of the woke left?

GRANT JOHNSON

You may not have heard of him, but many of his ideas have probably helped shape your latest views.

ALLAN RAY

Jagmeet Singh and the NDP lost touch with rising political trends and with working-class Canadians.

JOHN MILLER

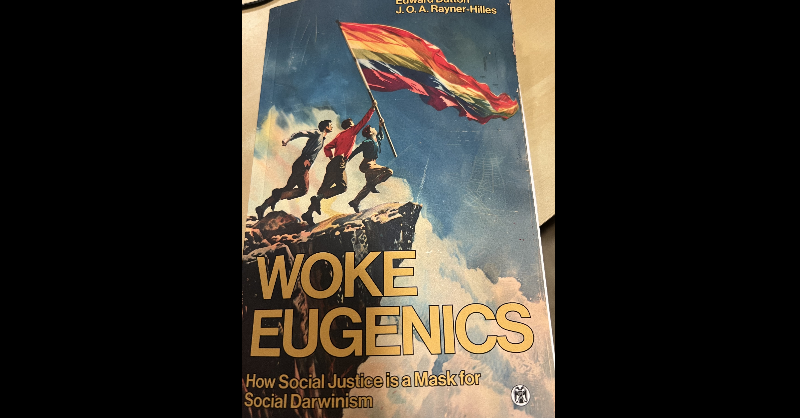

Any based conservative should find this series entertaining and fun to read.

DEVON KASH

Their headlines would have you believe that an innocent Canadian died in Trump's custody.

ALLAN RAY

The province is facing crises on several fronts, only a conservative mindset can undo the damage caused by the NDP.

RYAN TYLER

They would love nothing more than for the dissident voices to shut up and leave the country, but we won't.

MEGAN PRIESTMAN

Almost anyone and their dog can vote in the country's elections, which could have dramatic implications for the future.

STEVE PARKER

The way he has lied and fibbed his way to the top shows exactly how he feels about his own supporters.

MEGAN PRIESTMAN

The Netflix series drives home the reality facing white men in Britain and around the world, albeit, unintentionally.

GRANT JOHNSON

Conservative strength is the result of something else, and Canadians are easily propagandized.

MICHELLE ASHLEY

Liberal voters and media don't have a right to tell you to be less angry and to come together with your elbows up.

This is the same government, but it has a new face and a new scheme.

MEGAN PRIESTMAN

Soon, an offender's sentence could be decided by their racial identity, rather than the severity of their crimes.

STEVEN PARKER

Canadians have always been passive-aggressive, opinionated internet trolls living IRL.

STEVEN PARKER

Best friends and siblings can love each other, but what is the one thing that makes gay love "gay"?

RYAN TYLER

Think about a small handful of corporations and billionaire families controlling everything.

ALLAN RAY

Every single Liberal leader has been a white man. That doesn't look like it's going to change.

RYAN TYLER

The rapid influx of millions has caused devastation across several industries and to average Canadian households.

STEVEN PARKER

What do hippies and MAGA have in common? Oh, this is going to be so much fun.

THOMAS CARTER

Deportations and border enforcement are the correct ways to keep immigration lawful and fair.

GRANT JOHNSON

The inauguration of Donald Trump will only be the beginning of the good things to come in the new year.

RYAN TYLER

Cloverdale-Langley City and Lethbridge West show troubling results for the federal Liberals and the Alberta NDP.

THOMAS CARTER

The days of Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter are long gone. Today, it is just plain weird to be a Democrat.

POSTCANADIAN

History is filled with stories about new beginnings. The end is often the start of something bigger and better.

ALLAN RAY

Many are turned away by the idea of an emotional dictator who lives in the sky, but what if we could explain things differently?

ALLAN RAY

Trump has promised to unseal the documents, but has warned that Americans may not want to know what is in them.

NICK EDWARD

Trump played the media and his targets like fools, knowing they would build a mountain out of his mole hill.

These glaring problems suggest something different.

ALLAN RAY

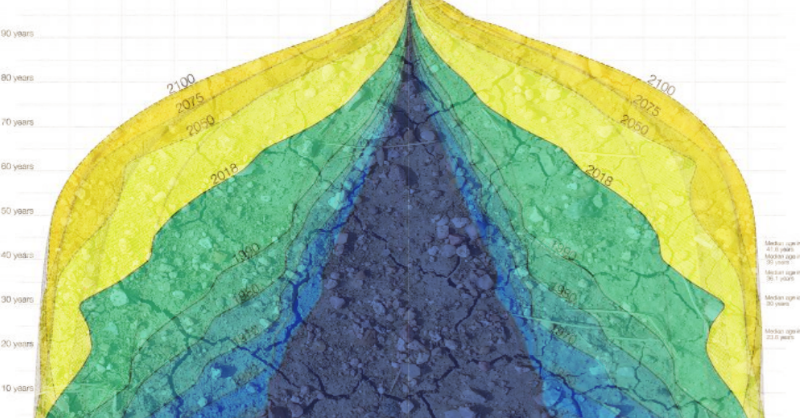

When you see it, you should be worried about your country's future.

NICK EDWARD

Choose your tribe, do not question the figurehead, obey, or be cast out.

RYAN TYLER

But what if we applied some feminist logic to these less convenient gender gaps?

GRANT JOHNSON

Liam and Noel have said and done some controversial things, but the band is reuniting for an album and world tour.

NICK EDWARD

If the unthinkable were to become reality, much of it might go exactly how we would have expected.

JOHN MILLER

The woke will go extinct as the survivors become ultra based. Is wokeness fixing civilization?

ALLAN RAY

Russia's KGB strongman is popular and has managed to make his country a self-sustaining global force.

DEVON KASH

If you like unravelling supernatural mysteries and ingesting some traditional conservative themes, you're going to like this one.

RYAN TYLER

A second shooter on a water tower? An FBI director in the crowd? Some of these theories are off the wall.

DEVON KASH

Even Kamala Harris is rumoured to be ready to jump in bed with the crypto industry before September.

ALLAN RAY

Violence has no place in a system designed around elections, peaceful transitions of power, and bloodless coups.